In Creative Confidence, Tom and David Kelly highlight that despite the expertise and history of success at Kodak, the company suffered from the knowing-doing gap, which prevented them from making the transition from what they had always done, to successfully navigating the shift toward the future of the industry. From their work with the leaders of Kodak, they describe what they observed.

For starters, tradition got in the way of innovation. Kodak’s glorious past was just too alluring. Kodak had essentially owned consumer photography for a hundred years, with market share in some segments as high as 90%. By contrast, digital ventures all seemed so risky, and Kodak wasn’t providing enough “soft landings” for managers willing to take career risks in those new areas. Facing strong global competitors in the digital market, Kodak knew that it would struggle, and fear of failure transfixed the management team. Caught in the knowing-doing gap, Kodak clung too closely to the chemistry-based business that had been so successful for them in the twentieth century, underinvesting in the digital world of the twenty-first century. What we saw at Kodak was not a lack of information but the failure to turn insight into effective action. As a result, on of the most powerful brands in America lost its way.

Are Traditions Getting in the Way of Innovation in Education?

I sat next to a group of high school students in Starbucks the other day and I couldn’t help but overhear their conversation. The four of them made room on a small table for their laptops and phones, while completing a photocopied study packet, which painted such a striking contrast in between their world and what was required of them in school. Although they were connected to the world and could look up any of these facts within seconds, they were stressed about “cramming for their finals” to show what they know. They acknowledged that they would never remember all of the information and they begrudgingly worked to complete their packets.

This example of high school students likely evokes a range of reactions that might sound like some of the following:

- This is how I learned and they need to learn this way too.

- They will need to know this for the next year or college.

- I always hated doing packets and I never give worksheets.

- My classroom is all digital and students are always connected.

- This is why I do create projects that are relevant to my students.

All of these reactions and more reflect a range of beliefs today about learning and school that have been developed based on one’s own experiences. Teachers are socialized in various ways including the observation of their previous teachers known as the apprenticeship of observation (Lortie, 1975), their preparation programs, as well as their colleagues and the context which they work.

These past experiences in school often reinforce beliefs and expectations about the teacher as the holder of the information and the need to be in control, yet this may be in conflict with today’s learners’ needs, opportunities, and skills necessary to thrive in a changing world. The tradition of school is so deeply ingrained and as many educators have been successful in the traditional model it can be hard to imagine doing it differently. But like Kodak experienced, we can’t hold on to our traditions just because they were successful then, we need to align our learning experiences in schools to meet the needs of learners today.

Teachers Create What They Experience

I often ask administrators and teachers this question:

Are you systems designed for people to comply and implement your programs and policies or are your systems designed to empower people to learn, improve, and innovate?

Usually, there is a long reflective pause and an audible acknowledgment that much of the expectations are based on compliance. The truth is that the dominating model of change in education is typically top-down reform programs or practices that have “worked” in another context and teachers are expected to replicate them in diverse contexts rather than learn about new methods and adapt them to their own unique context. This often results in compliance rather than learning, growth, and innovation.

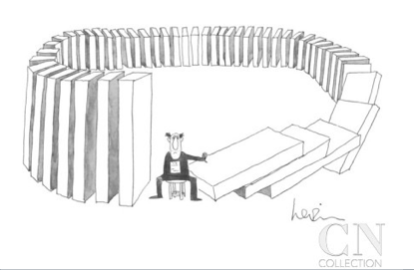

Consider this typical cycle–A principal is expected to comply with district mandates and in turn, she expects the same from her teachers, it will most likely be how the teachers treat their students. Students may comply but often lack engagement and certainly are not empowered and then we say our schools are failing and then we need to create new programs to fix the problem and create new mandates for principals and teachers to comply and then.. the cycle continues.

To realize the changes in schools, it will require more than providing training for administrators and teachers to implement new curriculum or programs and resources. The schools and districts I have seen the most movement have focused first on creating a culture where people have a common goal and are willing to share their strengths and challenges, take risks, and try new things to work towards that goal together.

In the Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge, describes how a learning organization encourages and facilitates learning throughout all levels of an organization in order to enable it to adapt and transform itself to function effectively in a complex and dynamic world. This means that professional learning cannot exist in a vacuum. How teachers learn and put new ideas into practice is heavily influenced by leadership, what is modeled and experienced, as well as what is valued.

Closing the Knowing-Doing Gap

In their book, The Knowing-Doing Gap, Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutton’s research highlights that “knowledge that is actually implemented is much more likely to be acquired from learning by doing than from learning by reading, listening, or even thinking.” To close the knowing-doing gap in schools will require shifting the culture from telling teachers about theory and best practices to creating opportunities and cycles of learning that ensure teachers not only develop new knowledge and expertise but use it to change how students learn.

I am always engaged and inspired by your posts. We have to do the work, not just think about it or watch others do the work. Leaders have to be co-learners with teachers, students, parents and community. It is too easy to direct; far more challenging to create the space for everyone to have the autonomy to do the work, thus experiencing agency and the inspiration to move forward. Super challenging, complex leadership work! Thanks for another post that gets me thinking deeply about the new kind of leadership we need in a learner-centered space.

I especially connected with the “typical cycle” you described and the trouble with the top down mandates in education. Learning is a very individual experience and creating a mandate that attempts to address the needs of each student is impossible, especially when the people creating the mandates never interact with the students. True success in learning comes from a educator who can present engaging and innovative opportunities for students that allow them to explore, create, and build on their individual passions.

I love how you talked about leaders being co-learners with everyone in the community. This would connect teachers, students, parents, and others. It is important that people understand that learning doesn’t end with just schooling either. Humans are continuously learning and it is important that more people realize that and put it in action. Great post!

Thanks so much for sharing your ideas; there’s a lot of stuff to consider. It got me thinking about a conversation I had the other day with a friend who is getting a principalship at a “progressive” school in America. The word “progressive” isn’t implying innovation, more of a desire to equity in education. So we discussed the first moves in moving the school into the 21st century in which students of all race and creed are being served. I think when you have schools that are really entrenched into their identity, shifting the culture can be problematic. Your ideas about “tradition” are spot on about that. Any thoughts about where you might begin when you have a culture of complacency? What would be your first moves?

Great post, Katie! And loving your new book – Evolving Education. Reflecting on what everyone is saying and asking – especially how to move beyond tradition and complacency;

It comes down to unleashing those who are the natural innovators – our kids! Let’s tap their inherent genius and passion to transform education into learning ecosystems!

Thanks, Mary! I’m glad you are enjoying Evolving Education.