“I don’t learn that way.”

Whether it’s my uber driver, a parent, teacher, student etc. it seems that more often than not in various conversations I have people tell me that they (or their children) don’t “learn that way” in reference to how we traditionally do school. People explain that they are visual or like to work with their hands or need to talk to others and try some things out, which they often explain, is not how they were supposed to “learn” in school. Instead, success was determined by sitting still, individually completing endless packets or worksheets, and providing the right answers on the tests.

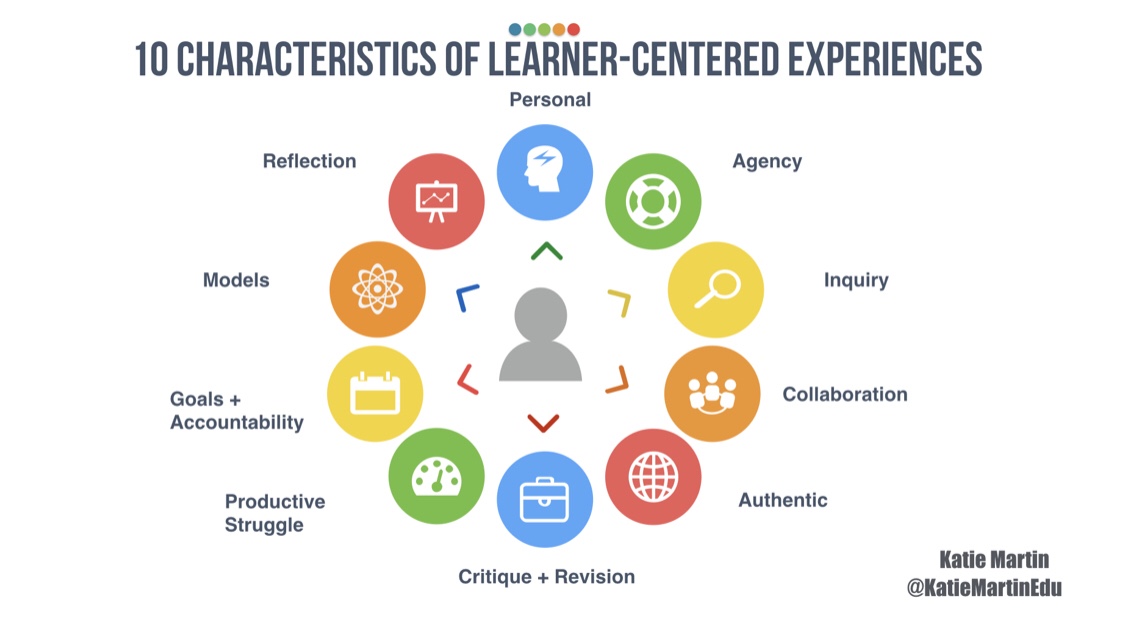

I am amazed (and honestly frustrated) that we have become so conditioned to believe that the way we do school in many cases is what’s right instead of the way many people actually learn. We have this widely accepted notion that there is something wrong with us (or others) because we don’t fit in the box of what is traditionally accepted as smart, instead of acknowledging that learner variance is the norm, not the exception. As I work with diverse educators and talk with students, there are common characteristics that always surface when people share powerful learning experiences.

Are We Educating for School or Life?

In my book, Learner-Centered Innovation, I wrote that “Despite the incessant focus on sorting and ranking, good grades in school don’t always equate to the highest levels of success in life (or happiness). Shawn Achor’s research at Harvard shows college grades aren’t any more predictive of subsequent life success than rolling dice, while a study of over seven hundred American millionaires showed their average college GPA was 2.9. When we focus on the grades and scores rather than the skills we are learning and more importantly what we can do with those skills, we are missing the point in schools. While academic environments tend to be more artificial.”

“Knowing” doesn’t make you good at something on its own, which is why doing well in school doesn’t always translate to succeeding in life. In school, there are often clear rules and a narrow path that defines success. Life does not work this way. In fact, high achievers in school often struggle to make their own way in an uncertain world. Yet, as many of us expected to go to school, follow the rules, get a job out of school, that path is becoming more of a distant dream as kids today will have to create their jobs and a new path. When we become so focused on compliance, improving test scores, and covering it all, it can prevent us from the larger goals of developing learners to think, communicate, and generate novel ideas based on their passions and skills.

The Future of Jobs Report describes the urgency to prepare future workers for the not so distant future. “The talent to manage, shape and lead the changes underway will be in short supply unless we take action today to develop it. For a talent revolution to take place, governments and businesses will need to profoundly change their approach to education, skills and employment, and their approach to working with each other.”

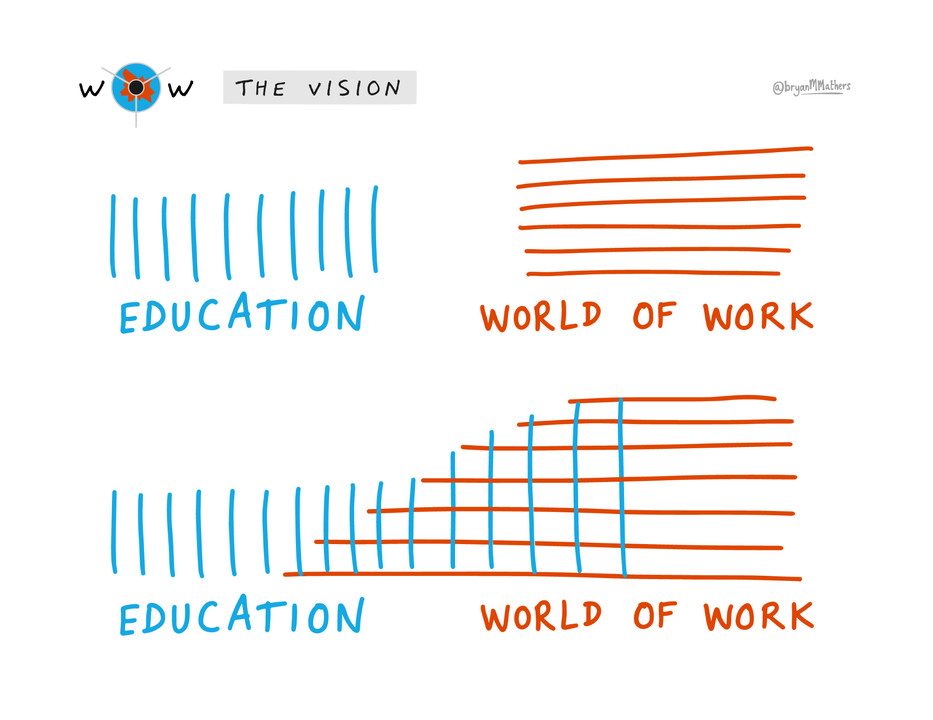

To support this necessary shift in schools, Ed Hidalgo shared how Cajon Valley’s World of Work Initiative, was “developed as part of the greater effort to make the Cajon Valley community the best place to live, work, play and raise a family. Central to the mission is the importance of jobs, and the goal of helping all children find their place in the world. This means helping students discover their unique strengths, interests and values, building skills and aligning them to authentic experiences in the classroom to prepare them for the world of work.”

The world of work demands individuals embody skills such as complex problem solving, critical thinking, and creativity. But if our actions in schools still rely on antiquated practices, we will fail to develop learners who have the skills to be successful in our constantly changing world. As Sir Ken Robinson says, “Education is not preparation. The first 18 years of life are not a rehearsal. Young people are living their lives now.” It’s critical that we rethink why, what, and how we learn in schools for students to thrive in the information economy of today and tomorrow, not yesterday.

What is your response to people who claim “I don’t learn that way” to non-traditional approaches? I have observed when educators do offer real-world simulations and prioritize process over product (the grade), there is push back from both parents and students. One student even claimed, “I like book work,” which I knew in this case was a statement founded on the basis of risk aversion but easily wins the support of parents, and sometimes even peers, colleagues, and administration. But, especially parents (I think..) because that black and white letter grade on a vocab test is much easier to comprehend than an in-depth progress report on communication skills.

Curious to know your thoughts, hope I haven’t overlooked them somewhere on this blog. Always great posts, keep it up!