There is an increasing trend of parents clearing the path for children and removing any barriers within their control that could make things more difficult for their children i.e the college admissions scandal, which is also known as lawnmower parenting. This is typically done with the best intent and although I don’t love labeling people like this, some of these practices have real implications for how children develop that we should be aware of. In this article Why Lawnmowering parent is actually Robbing Your Children, Kelley Kitley, a licensed clinical social worker, provides a few examples of lawnmower parenting on a smaller scale than actually committing crimes but that still have detrimental effects such as “pulling strings to get your child onto a certain sports team, setting up a rigorous summer schedule that is all work and no play to get ahead or If a child fails to complete a homework assignment, a mild lawnmower will say her kid is sick so the child can use the time off school to get the project done.”

Although many educators are quick to lament this type of parenting as it interferes with their teaching, we aren’t totally removed from it as educators (especially since most of us educators are also parents.). As a parent myself, I acknowledge that it’s hard to know the right balance as I, along with many parents, want our children/ students to be successful and so of course, if we can remove barriers it feels like it is the right thing to do… but is it???

In the same article noted earlier, the author also notes, “Kids who receive the best of everything and don’t have opportunities to practice defeat will later struggle when coping with life’s messy nature.”

This is true in education as well. In Limitless Mind by Jo Boaler she highlights the TIMSS study that found that the mathematics curriculum in the US is “a mile wide and an inch deep” compared to the curriculum in more successful countries. One of the major findings when researchers observed classrooms was that Japanese students spent 44 percent of their time “inventing, thinking, and struggling with underlying concepts whereas US students engaged in this less than 1 % of the time”.

I often question if we are over-scaffolding learning for kids and this study reinforces that the answer is often yes. Boaler shares her observations, “Many times I observe students asking for help and teachers structuring work for students, breaking down questions and converting them in easy small steps. In doing so they empty the work of challenge and the opportunity for struggle. Students complete the work and feel good, but learn little.”

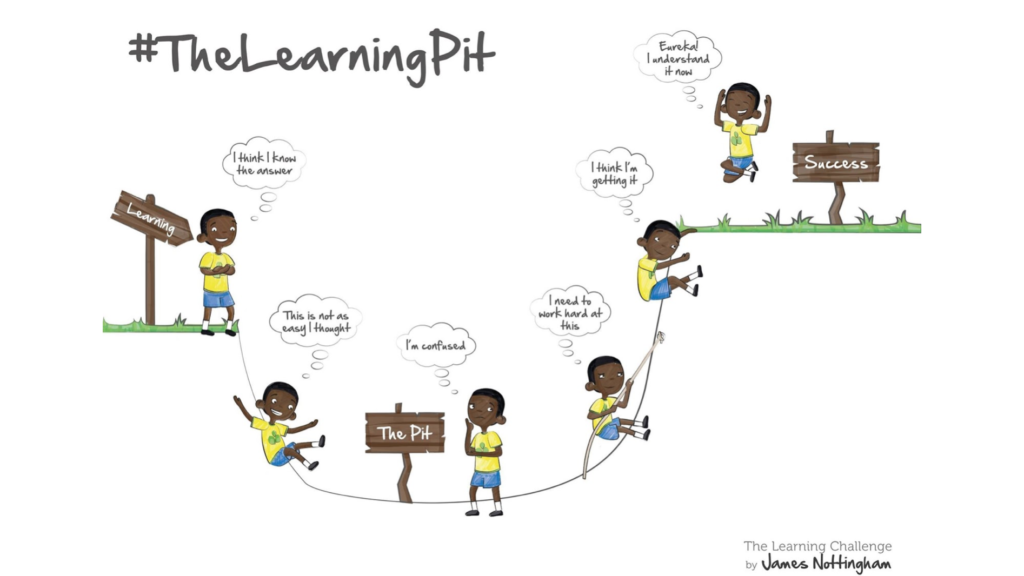

I have seen this same thing as I visit classrooms and talk to teachers and often it is out of the desire to help students succeed and remove barriers but we end up doing the learning ourselves rather than allowing the students to struggle and learn themselves. James Nottingham describes this as the Learning Pit and more than anything, we need students to understand how to navigate challenges, develop strategies, and push through to emerge with deep learning and the ability to learn to learn.

Just to be clear, when I refer to over scaffolding I am not advocating for abandoning students to figure it all out on their own. I believe in the power of teachers and peers and learning in community, not saving it for homework and relying on the supports students have —or don’t — at home to help. Since we often can categorize practices as black and white in education, here is an example of the opposite of over scaffolding that doesn’t serve students well either. I have had many parents and students tell me that they don’t get taught during school anymore and they have to come home and learn it themselves or have parents teach them. This has become more common as the “flipped classroom” became popular. At times it feels to students (or gets misconstrued) as “Google it” and figure it out or watch this video and learn on your own instead of providing targeted instruction, support, and collaboration to work through problems and learn new concepts, strategies, and skills rather than complete assignments. Teachers who provide guidance, encouragement, checkpoints, and ongoing feedback are critical to the learning process.

Here are some things to consider when you are designing powerful learning experiences that meet the needs of all students:

How can I provide more opportunities for inventing, thinking, and struggling with underlying concepts?

I met a student this week at Design 39 and she shared her experience as a new student in comparison to her previous school. I love here simple comparison, “At this school, I get to draw it out and estimate and collaborate instead of just doing a string of problems. I feel like I have grown so much from this. Instead of doing a sheet of work by yourself, you work with other people and develop respect for one another” This was a 3rd grader by the way! When I asked what advice she would give her previous teachers she said: Let us work on problems and give us time to figure things out. Try giving less but more complex problems. Let students try to solve them, share their ideas with their peers, mess up, fix their mistakes and embrace the struggle and power of perseverance. Teachers can help identify effective strategies, pinpoint mistakes, and push learners to invent, think and struggle to grow.

What does this learner need now rather than what is in the script or the plan?

This. is. hard. I remember my first assembly and how it threw off the perfect balance of each of my middle school classes being at the same place. Still in weeks 2 or 3, I had this notion that I could keep each class, let alone each student at the exact same place and that they would all just move along the path at the same time and place. Ha! One of the most powerful lessons I learned is that we are all at different places in our learning, motivation, and goals and we always will be (just check in with your colleagues down the hall). This doesn’t mean that we don’t have goals and accountability, it just means we have different paths to get there. It’s super important to celebrate growth in learners based on where they are— and ok that they aren’t where everyone else is. Creating checkpoints, deadlines and milestones are helpful for learners to track progress and ensure there is forward progress but each path and pace may vary, and that is ok. #deepbreaths

How can I help learners understand the goal and give them tools to navigate the path and track their own progress?

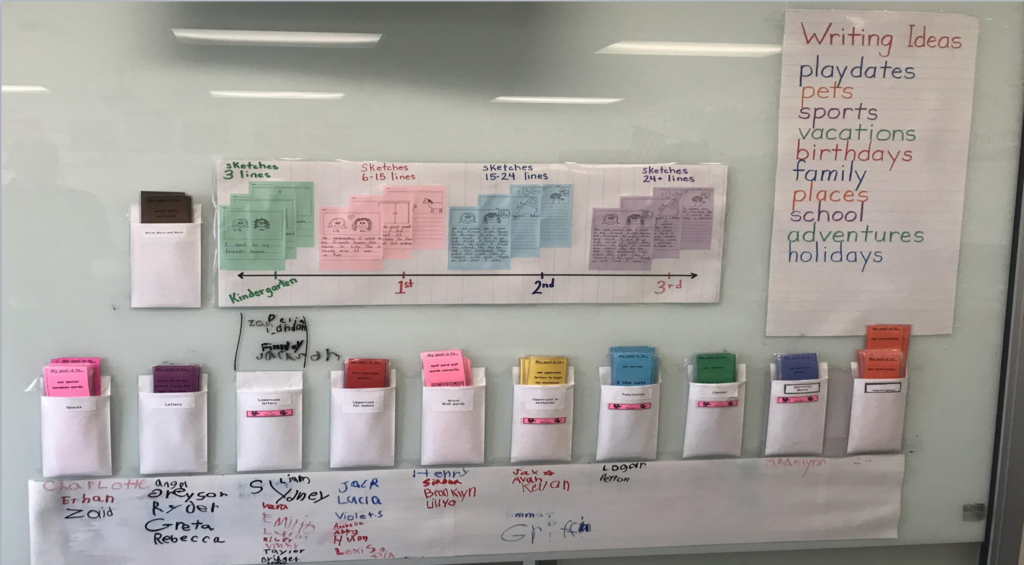

Before providing scaffolds and support, allow students to demonstrate what they know (and what they need support with) before you assume they all need the same thing. I love this example from Kettle Morraine School District. In an early elementary mixed grades classroom, students are provided models of proficiency in various competencies and they can identify their level of proficiency with respect to the desired goal, set goals with the support of their teachers as needed, and work towards them. When learners know their goals and have support and resources to get there in a way that meets their needs, they are more empowered and empowered to achieve their goals. Think about this in your own growth as an educator. Which is more empowering— Someone evaluating you (likely not in context or in your best light) and telling you what to improve or would your rather identify the desired goals, self assess, set goals that are based on your needs and work towards mastery in a way that works for you as a learner, with necessary resources and support? If this can work for young kids, it can work for all of us:).

Now What?

As you reflect on your aspirations for what you want learners in your classroom, school or district to do, consider where you are in the learning journey? What are your strengths? What are your challenges? What are your goals? As you think about your own journey as an educator and the impact it is having on your students and their learning, it is powerful to model your own successes and challenges so students know they are the only ones who go through the learning pit.

If you have examples, ideas and even questions, please share and help us all grow.

I am a Special Education teacher who co-teaches in two math classes. The gold standard for teaching math to students with math disabilities is to use explicit teaching with lots of practice. When a lesson has a low floor, students with IEPs can engage with the material. But in many cases, the lesson causes them to simply give up. I’m looking for ideas about prompting students during those moments of frustration to help them experience productive, rather than destructive, struggle. Thanks!!

Hi Audrey,

I also am a special education teacher struggling to introduce grit and productive struggle. Some of Rachel Lambert’s research might be useful to you, especially her paper *“Indefensible, Illogical, and Unsupported”; Countering Deficit Mythologies about the Potential of Students with Learning Disabilities in Mathematics*. As far as instructional techniques in the classroom go, I am finding there is nothing that can work until there is a shared understanding between teachers and students that the struggle is good and that it is a necessary part of learning. Jo Boaler has a lot on this and I think that part six of Peter Liljedahl’s Thinking Classroom framework (https://mslwheeler.wordpress.com/2017/03/15/building-thinkingclassrooms/amp/) might be a good place to start if you are looking for really concrete instructional things you could do.

I noticed your examples in this piece are from elementary schools. There are some common elements to productive struggle across all ages, toddler to adult professional, but I think the differences are important in defining how to support it successfully. Not only in terms of where students are in there journey when they are in high school, but also where parents are at that stage, how can we effectively engagr in this practice assuming little or no intentional practice with productive struggle?