Students need to grapple with problems and own their learning, and the same holds true for educators. The rally cries are clear: If you want to see learner-centered practices in the classroom, we need learner-centered professional learning. Educators are looking to develop skills, particularly in areas based on their own content area, skills, and goals. Learner-centered professional learning should honors the needs of educators as professionals while addressing the larger goals of the system.

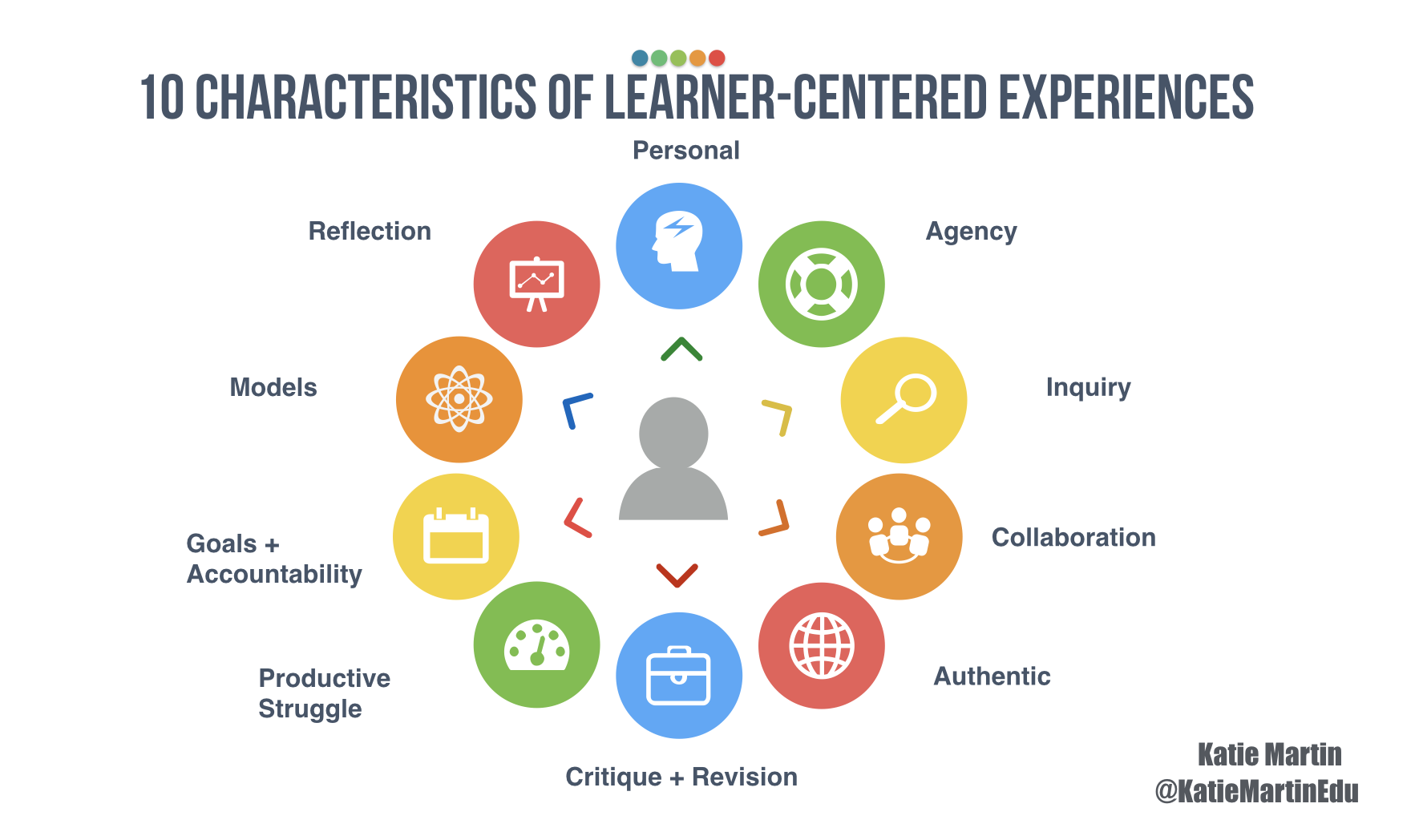

I recently wrote this post 10 Characteristics of Learner-Centered Experiences and many people have asked me about professional learning would support educators to create learner-centered experiences. These same characteristics of learner-centered experiences that we want to see in classrooms should be present in professional learning as well. Educator’s beliefs, knowledge, and skills are shaped by their experiences both past and present, and often these get mirrored in their classrooms and in their leadership practices. The following are a few examples and ideas from my upcoming book, Learner-Centered Innovation: Spark Curiosity, Ignite Passion, Unleash Genius, which is set to be released early February!

UPDATE: The book it out. You can get it here!

Personal

Too often for the sake of convenience, we mandate training or professional development for all when it only pertains to a few. Diverse contexts and areas of expertise require flexibility to meet the desired goals and support individuals along the path. To support learner-centered innovation, ensure that the learning is connected to the content, experience, and resources of those in the rooms and connects the students they serve. We need to allow for diverse paths and outcomes to support learners to move forward from where they are to where they want to go.

I’m encouraged to see many districts and individual schools moving away from the large-session, one-size-fits-all format and allowing educators as learners to have more choice in a variety of sessions. I have also seen some alternatives to stand-and-deliver sessions and information-heavy staff meetings, such as flipping faculty meetings or providing choice options for an all-day district professional development day. This focus on voice and choice can lead to more engagement in sessions. But we can’t stop there. To integrate new ideas into practice, we can’t just change the format of the meeting to make them more exciting or find a different way to share information. If we aren’t clear on our desired outcomes, what we believe about good teaching and learning and fail to create the time and space for teachers to learn and try out that learning with their students in their unique context—based on their needs and goals—we will not see the “training” translate to learning and ultimately better outcomes for students.

Agency

In the Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg provides an example of assembly line workers who were provided an opportunity to make decisions about their workday. They were allowed to design uniforms and make their schedules. Two months later without any pay raises or other changes to their work environment, productivity increased by 20 percent. Workers were taking fewer breaks and they were making fewer mistakes. Giving the employees a sense of control impacted the level of self-discipline, focus, and energy they brought to their jobs. This same phenomenon applies to educators and the students they serve. If we engage learners in experiences that allow them to solve a challenge that is meaningful and relevant to their context, they will be more empowered to devise a solution and take action to make the desired improvement.

Brad Gustafson, a principal, and author of Renegade Leadership, shared a great example of how he shifted a traditional professional development day for his staff to model the type of teaching and learning he wanted to see in the classroom. He started by collaborating with his staff to design a day that was built on the school goals and priorities. Together, they leveraged research-based practices and gave teachers choices on the topics they wanted to grapple with based on challenges that were most meaningful to them. This learning experience, which took place within a four-hour period, focused on relevant topics and built on previous learning to sustain momentum and go deeper. The goal was to drive the change they want to see in their school.[3] This intentionally crafted day of learning provides a great example of balancing the system goals while allowing for individuals to get what they need.

Goals + Accountability (based on competency, not seat time)

In his book, Where Good Ideas Come From, Steven Johnson notes that “innovative systems have a tendency to gravitate toward the ‘edge of chaos:’ the fertile zone between too much order and too much anarchy.” If we want innovation in our schools—and we should—we have to create systems that live in this fertile zone. When we are too rigid and demand compliance, we leave little room for creativity nor opportunities to be innovative. On the other hand, when we lack the vision and support to get there, many feel lost without a clear direction and revert back to what they have always done. To balance the goals of the system and the personal growth of the individual, we need to provide a clear vision and the structure for individuals to learn in a way that aligns the system goals and personal goals.

Kettle Morraine School District in Wisconsin, led by Superintendent Pat Deklotz, has been a pioneer in this work at the district level. The administration worked with teachers to listen to their needs as they moved toward a new vision of teaching and learning. Pat shared, “We took deliberate and thoughtful action, listening to our teachers, and aligning their interests with our system’s need to attract and retain high-quality staff. We wanted to provide opportunities to recognize the differences in the professional development needs of our educators and for them to experience personalized learning themselves, in a competency-based model.”[2] By offering personal pathways and using a micro-credential system to assess, track, and reward the development of desired competencies, teachers have been empowered to drive their own professional growth. In a blog, Mr. Anderson, a teacher in Kettle Morraine shared that, “Micro-credentialing has changed, for the positive, how educators are viewing their own professional development and career path—it has enabled educators to personalize what it means to be a career educator for themselves and their classrooms.”

A competency-based system allows educators to demonstrate proficiency in areas where they excel and seek support and guidance for specific areas of growth. Similar to demonstrations of student learning linked to mastery, competency-based professional learning allows leaders to identify the expectations, co-construct the goals and create for personal paths to develop and demonstrate mastery of desired competencies based on needs and context in which the educators teach.

Inquiry-based

Learning to better understand the challenges I am facing and then generating and testing new ideas has allowed me to own my learning and has provided me with a sense of agency. It is so empowering to see the results that come from putting what you are discovering into practice!

An inquiry-based approach to learning and improvement, commonly known as improvement science, aims to engage learners in rapid cycles of Plan, Do, Study, and Act (PDSA) to learn fast through action, fail fast, and improve quickly. This approach acknowledges that failure is part of the process and that failure itself is not the problem; failing to learn from the process is where we can go wrong. Improvement science empowers learners to make tweaks as they investigate ideas. For educators, this model of discovery, exploration, and doing allows us to continually improve the way we serve the learners in our specific context.

Amy Var, a middle-school teacher, engaged in an improvement science project to figure out how to enhance her peer-editing process by teaching students to give more thoughtful feedback. After learning about a variety of strategies, she thoughtfully implemented a few, including editing in Google Docs, to allow for more fluid commenting and editing. She found that this tool empowered students to invite outside collaborators to make comments on their writing. It also allowed her to collect evidence to determine the effectiveness of the tools. As Amy learned to use new tools and saw it working with her students, she let go of the control of editing and became more willing to allow her students lead. The evidence she collected included student work, student feedback, and her own observations. She embraced the role of the learner and shared her thoughts on her blog on the process:

More than anything, I’m looking forward to our next steps. I feel like I started by dipping my toe into the pool, and now I’m ready to dive headfirst into the waters of change and see where the tides continue to take me. It’s such a good feeling, after eighteen years of teaching, to be this excited again!”

I want to underscore her reflection. With so much focus on how to motivate and incentivize learners, Amy’s personal learning experience illustrates that when what we are learning is directly tied to our own goals and is meaningful in our daily work, learning can be its own reward and can push us to want to know more. When learners are empowered to work through issues that matter to them rather than just going through the motions, the time and energy spent isn’t a chore; it’s productive because it improves both job performance and satisfaction.

Collaboration

You can have all the right structures in place, but if you haven’t built the relationships and created a community with shared goals where the individuals feel valued, none of it matters. If we don’t invest in the relationships and build connections between people and our ideas, we limit the potential of what we all can achieve together. High-functioning teams value the team as a whole and understand the relationships are at the core of the work. They ensure they invest time in building those relationships to best serve the team so that they accomplish the desired goals. A willingness to ask for and receive input characterizes the best teams. That vulnerability shows that the team members respect one another’s opinions and are willing to incorporate diverse viewpoints to become more productive and efficient. In schools where empowerment and collaboration are norms, teachers often have higher morale and stronger commitment as well as the desire to remain in teaching.

This quote from Henry Ford captures the difference in calling yourself a team and working together as a team: “Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.” We have become accustomed to showing up at team or staff meetings and counting that as our duty, but showing up is not success. Showing up is the first step. Coming together as a team and pooling our expertise to develop ideas that will improve outcomes for all learners is what we should be working toward every day. We have too much to do, and the stakes are too high to go at it alone.

Authentic

After engaging in a Personal Learning Challenge, one teacher highlighted the impact of publishing her work and the power of an audience. “I was skeptical about this project and how it would impact my learning if all I was talking about was running. Then I posted my blog on Twitter and Facebook, and I started to receive a lot of feedback. I realized that publishing work brings a different level of accountability that I had never expected. You know you have a wider audience to critique but also to support.”

Another teacher noted that, throughout this process, she was most struck by the support network that helped her achieve her goal. “Whether they came up to me with advice, posted articles on my timeline, or commented on my blog, I had a support group that would not have existed without social media. I also felt motivated to succeed because I had so many people checking on my progress. If I can use these resources and have my students publish their work, it will have a huge impact on their learning.”

Creating structured opportunities to be metacognitive about how and what you are learning can inspire the creation of new learning experiences for students. Throughout the Personal Learning Challenge, teachers began to see the value of the vast resources online as well as the variety of opportunities that exist for learning. Beyond the resources, they also experienced the power of connecting across diverse networks. Most importantly, they see the possibilities for their own students and are able to imagine ways to bring those learner-centered experiences to their classrooms.

Critique + Revision

A fairly common practice is to share activities and showcase the final products produced in classrooms, but when it comes to delving into what is working and what is not, many teachers are not used to this level of transparency in their practice. Only when we are open to exploring the challenges we face can we develop better experiences for those we serve. To improve teaching, we have to focus on what students are learning. To go beyond discussing lesson plans and curricula, looking at student work helps educators understand how students apply what they are learning and focus on the actual impact of the teaching.

Presenting challenges, providing feedback, and creating actionable next steps are all valuable exercises that help improve learning experiences. Teachers can benefit from presenting a lesson idea or project on which they are just beginning to hear feedback. Midway through a project, you can seek feedback to help improve and determine next steps. In my experience, one of the best ways to understand and provide feedback to improve teaching and learning is to look at student work samples from your own projects. When educators look collectively at student work to determine strengths and implications for designing learning experiences, we can learn a great deal about our impact on desired learning outcomes and discover ways to improve.

Productive Struggle

There is a tendency to model step by step and ensure we provide clear directions for how to do everything. We often feel like we aren’t doing our jobs if we don’t take people through the process and teach them every single step. In reality, this often limits creativity and ownership in the learning.

As I worked with a group of leaders, I asked them to create an elevator pitch in a video to communicate their ideas. They had to plan what they wanted to say, work with their group, figure out an app and record something… in 30 minutes. Instead of walking everyone through the process together, I pointed them to the link and communicated the goal and the timeframe and allowed them to figure it out. There was frustration, there were questions, mistakes, and challenges but in the end, they figured it out. And at the end of the 30 minutes when they reflected on all the steps and what they accomplished as a group and individually they were proud and empowered to keep learning and exploring new things…on their own.

Creating an environment where educators have permission and feel encouraged (and expected) to take risks in pursuit of learning and growth rather than perfections is absolutely foundational to shifting practices.

Models

A school leader shared with me that, although she felt her school offered ample professional development, she was frustrated that there hadn’t been a dramatic shift in the classrooms. She had hoped to see an increase in students solving authentic problems and using applications to have deeper learning experiences. Instead, students used technology to upload and share information or to complete assignments that looked very similar to the work they had done without technology. In response, I asked the leader to describe a typical professional learning day. She told me that, in every after-school meeting, she showed teachers how to use different apps; in fact, she constantly shared tips on new apps and tech tools she came across. What puzzled her is that the teachers seemed encouraged in the meetings and even shared their own ideas.

As we dug deeper into why the training wasn’t translating into the classroom experience, she realized that her teachers were doing exactly what she had modeled for them: They were using new tools to do the same activities and teach the same content they always had. Although they liked learning about new tools, they didn’t connect them to student applications for different or deeper learning.

Reflection

Reflection (and even more so, open reflection) is often put off if we don’t make time for it. Most teachers, however, understand the value of reflection and how it helps us improve. Blogging and even quick shares on social media provide an opportunity for self-reflection and then takes those reflections public where others can read, critique, and learn from us. It also gives us an authentic audience and level of accountability that pushes us to think through our ideas even more and to be open to accepting feedback in order to push our own thinking. Knowing that we have a wider audience to critique and support us empowers us to try new things, take risks, and hopefully lead us to innovate to create better experiences in our schools and classrooms.

Learner-Centered Innovation

In education, we have a lot of systems that run smoothly because we have been doing them—for years. The problem is that when we work with the same people, doing the same things, ineffective practices are rarely challenged or changed. Traditions and habits don’t inspire new ways of thinking for educators or for students.

By maximizing the multiple and diverse resources available, we can rethink the traditional model of professional learning to chart unique pathways and reach desired goals. Valuing the differences in teachers and immersing them in learner-centered experiences in professional learning is an essential lever that will allow educators to design similar learning experiences for the students they teach.

I love the “edge of chaos”!! Thanks for the great article full of research and ideas!

Hi Katie

At our university, some of us are trying to change the vocabulary away from professional development to professional learning – that’s what attracted me to your article.

However, it seems as if you are using ‘development’ and ‘learning’ interchangeably. IS there a reason for?

Our thinking is that things are developed, but people learn. Also, when I’m the professional developer and you’re the participant, there’s a bit of a condescending ‘I’m developing you’-thing going on. If I’m a participant, and I’m being developed, I don’t have agency, the developer has. But if I’m a participant, and I’m learning, I have the agency.

Your thoughts?

Hi Gerrit-

I absolutely agree with your thinking. I am curious how you see me as using learning and development interchangeably. It’s great feedback and not at all my goal.

Thanks,

Katie

Hi Katie

Thanx for responding kindly.

If I may use an example from the first sentence of ‘Personal’: “Too often for the sake of convenience, we mandate training or professional development for all when it only pertains to a few.”

I may be overly sensitive, but we would say “…training or professional learning…” We still occasionally lapse a bit into what we think is teacher-centric ‘development’ vocabulary, but we try to make a point of not using ‘development’, replacing it with learner-centric ‘learning’ vocabulary instead.