I was once asked, “What would you do with four hundred students who don’t want to learn?”

I took a minute to process what she was asking and realized that one of the challenges the whole she was working with was facing was rooted in these assumptions rooted in this very question. If we look beyond schools and at students’ daily lives, we may well realize that they are learning more than we give them credit for. Many are learning to play video games; some are watching and learning from YouTube, and some are creating their own videos. We are innately curious as humans and are hard-wired to learn. They are connecting and sharing things on social media; they are learning how to act and react by the models and interactions they have with peers and adults. I don’t believe it is learning that they are against, but it is true that many aren’t interested in how learning is prescribed in schools.

This question came as the team discussed their dream of providing an education that prepared their students for “college and career.” They hoped to ensure their students were eligible for college, but they were frustrated by the seemingly insurmountable gap in their students’ skills and where they needed to be. These leaders were all working so hard to prepare students for college and had been creating extra courses and opportunities for students to catch up, but in spite of their efforts to provide extra support, students were literally running out the doors to leave school and avoid the after school support. What they perceived as student apathy toward college preparation was the norm. What they hadn’t considered was why the extra classes and support weren’t achieving their desired outcomes or that there might be another way.

The hearts of these teachers and administrators are in the right place. They are committed to these kids, but their practices were not achieving the desired goal. What might happen if we reframe the question and look at this challenge from a different perspective?

Instead of assuming that students don’t want to learn, could we ask, ‘What is preventing students from learning in school?’

Many of these leaders had been successful in school. They did not understand their students’ lives or experiences. From their perspective, they were going above and beyond to help their students and teach them everything they needed to be successful. With a sincere desire to see their students succeed, they diligently implemented the district and school initiatives. They gave formative assessments, analyzed data in their professional learning communities (PLCs), retaught material, and provided extra classes and support. Still, less than 50 percent of their students were “proficient” on the standardized assessments, and less than 35 percent of them were eligible to attend college. They were doing all that was expected of them—and more—but it wasn’t working, and they were frustrated.

A Learner-Centered Approach

To better understand learners, rather than assuming we know what they need and why they are acting a certain way, we can better understand them and refine our practices as necessary when we honor diverse voices and empathize with them. IDEO, a global design company at the forefront of change and innovation, utilizes the human-centered design approach to meet the needs of its users. They define this approach as, “building a deep empathy with the people you’re designing for; generating tons of ideas; building a bunch of prototypes; sharing what you’ve made with the people you’re designing for; and eventually putting your innovative new solution out in the world.”

This human-centered design approach runs contrary to the typical standardized approach taken by our current educational system that views learners through a deficit-based lens. In the standardized approach, educators must work to fill students with knowledge or skills to help them reach the desired goal, be it the next unit, the next grade, or prepared for college. Empathy for the end user (learner) lies at the heart of human-centered design; this essential skill allows the designer to better understand the end user.

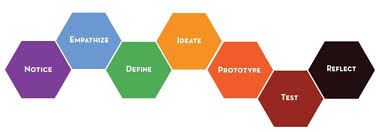

In collaboration with d.school’s k12 lab and the National Equity Project, the Liberatory Design process includes notice and reflect to the design thinking process to ensure that we understand the context in which the problem exists and reflect on the process.

With the Liberatory Design thinking process as a guide, we worked with teachers to first notice the context and then gather insight about how to design their lessons better and empathize with the learners. Instead of designing from their own perspective and understanding of the problem, they examined the context and spent time noticing and interviewing their students. Throughout the thirty-minute interviews, educators asked students questions such as,

- What is school like for you?

- Do you feel valued? By Whom?

- When do you feel successful inside the classroom?

- When have you felt unsuccessful?

- How might you improve this school?

In one-on-one or small-group settings and by asking open-ended questions and intentionally listening more than talking, they discovered a lot about their students. Through these interviews, teachers heard some ideas for improving their lessons, but what stood out most to them was that the schedules and class sizes contributed to the lack of meaningful interactions and that students felt insignificant in their classes. They also learned that students felt disconnected from their coursework. One student said he felt as if his classes and school were “irrelevant.” These interviews made a huge impact on the teachers’ ability to see school from their students’ perspectives, and the insight allowed them to think differently about what they perceived as the problem. Although they had perceived the problem as poor behavior impacting academic achievement, they were genuinely surprised and saddened to realize that a significant percentage of their students were disconnected from their own academic experience and the reality of their not-so-distant futures.

Based on the students’ responses, the teachers began to understand that relationships were at the heart of their challenges but could also be the solution. Students wanted to be seen as individuals and valued for their unique strengths. The teachers now understood that developing relationships had to come before developing the skills and knowledge necessary to put them on the college and career path. This new vantage point allowed teachers to consider different solutions.

Rather than adding more coursework and remedial programs, they began to brainstorm models for mentoring programs, advisory classes, student portfolios, and other opportunities that fostered relationships while making meaningful connections between learning and the students’ personal interests. The student engagement that resulted reignited these educators’ energy and passion by reminding them why they began teaching in the first place: helping students thrive.

Content Does Not Change Behavior

Imagine that, instead of interviewing students and creating the solution to meet the desired goals, the teachers spent their professional development time reading about advisory and portfolios. What if they explored the curriculum and learned about a new program for students to upload their work and were then asked to try these programs over the next month? How many do you think would actually take the time to do so? My guess is, not many. The new program would likely have been seen as adding something else to their already busy schedules and would have caused frustration and burnout rather than inspiring teachers to connect with their students. What made the difference for the teachers and students above was the connection made when they realized how and why the changes would meet their students’ needs.

This is an excerpt from my book Learner-Centered Innovation.

0 Comments